That is why tires are designed specifically for the Corvette — N44 nylon cord — good for sustained 140 mph driving and they are used on no other American car. Duntov knows it is against the law to travel at that speed in every state but one and he doesn’t care. If any Corvette driver, for whatever reason, should have occasion to drive at 140 mph the capability to do so safely should be built into the car. It’s built into the suspension; the Corvette has more suspension travel than any other car manufactured in this country. If Duntov and the engineers desired, this travel would allow them to make a soft ride — softer than any of the performance cars — but then the Corvette would be likely to bottom out at high speed and it would be unstable. So the ride stays hard even if there is excessive travel by Detroit standards; that’s the price you pay for 140-mph capability.

The same design priority comes out again and again in discussions of brakes, steering, aerodynamics — the concern for the Corvette driver who may some day run his pinched-waist two-seater up to the redline and hold it there. Traditionally, top speed is something that only European car builders worry about. But when Duntov speaks, and you break your concentration on what he is saying long enough to notice how he says it, you know that he is closer to them than us. Although born in Belgium, he is a Russian, and all of the years after he left Russia — studying engineering in Germany, occupying his spare time with racing motorcycles and cars; the years in Belgium and France working on race cars and the highest output engines of the day (often supercharged) — have had as profound an effect on his automotive philosophy as on his accent. And his accent is a hardened alloy of old world structures and formations that 30 years in the United States seem not to have scratched.

So you focus on the way he says his words, a way that is his alone, and you feel the intensity of his commitment to the Corvette and to engineering it to a level of performance surpassing all of the volume production cars in the world. Then, almost without noticing the transition, you find yourself in Nevada with the tachometer just a needle-width away from the red zone. The speedometer reads over 140 mph and you know that everything is all right, if it can ever be all right in any car, at that speed, because Zora Arkus-Duntov would settle for nothing less.

|

|

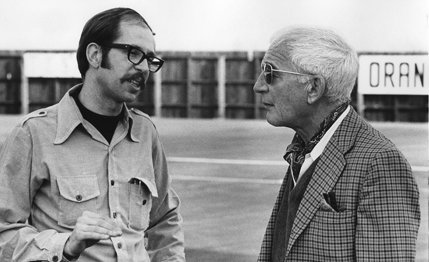

Obviously this is no ordinary road test. But then how could it be when it’s about a man so rare and complex as Duntov and about cars so Detroit-yet-European as the Corvette. At this point it would be the worst kind of irresponsible journalism to say that Duntov is personally responsible for every nut, bolt and forging in the Corvette — dozens of Chevrolet engineers work on it. Still, over the years, it has been his vision of what a high-performance sports car should be that has transformed the descendants of the bulbous, indifferent 1953 Corvette into a two-place touring machine that can be successfully raced in the international GT category. So when you can have him — Chevrolet Chief Engineer-Corvette — present at the test to drive and explain why the 1971 Corvette behaves the way it does, the results have to be more meaningful.

The project was simple at the start. Every year for the last five years C/D readers have voted the Corvette as Best All-Around Car in the world, bar none. Any car with that strong a rating deserves an in-depth review. That means all of the Corvettes, one with each engine. And a little patience, for unless you plan months in advance, having the whole cast show up in one place on one day is impossible. We settled for two on one day and three a few weeks later — the LT1 being in the line-up twice — and were fortunate in having Duntov present for both sessions.

View Photos

View Photos

Leave a Reply